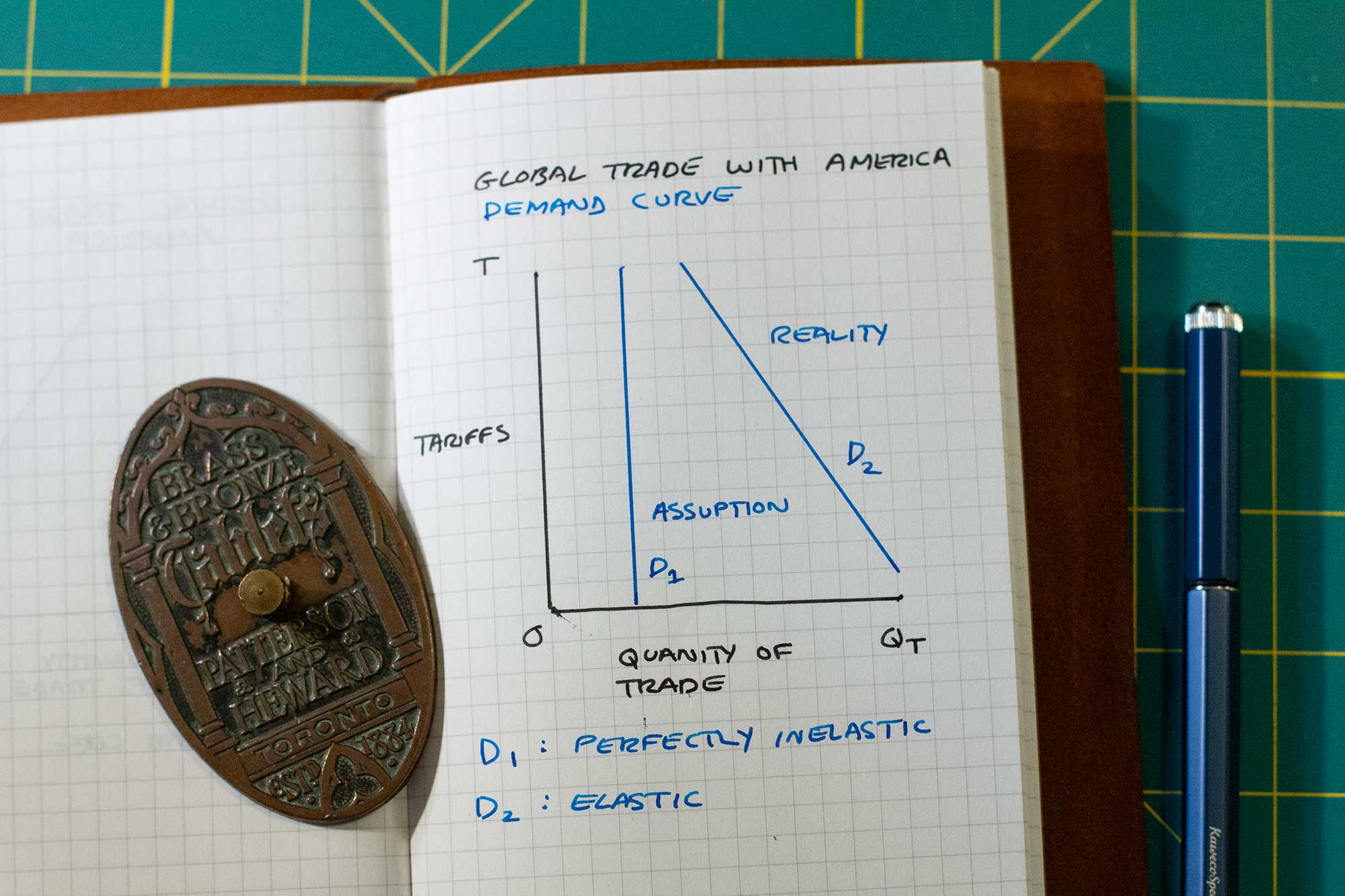

Why Global Trade Is More Elastic Than America Thinks

By announcing tariffs against nearly every major trading partner simultaneously, the U.S. didn’t just strain relationships, it introduced dozens of potential partners to each other and gave them a shared reason to collaborate.

As I’ve been following the news on American trade and tariffs, something’s been taking shape that is becoming clearer by the day. There’s a flawed assumption baked into the current administration’s global tariff strategy:

That demand for trade with the U.S. is perfectly inelastic. The world will continue to do business with the United States, regardless of the terms.

That idea might hold in isolated, one-on-one disputes, where a smaller country hesitates to jeopardize access to the U.S. market. However, it falls apart when the U.S. targets the entire world simultaneously. When that happens, trust breaks and elasticity appears quickly.

Canada is already exploring new alliances. Citizens are boycotting U.S. products. Other nations are quietly rebalancing supply chains—not just because of price, but because of volatility. Trade, like any relationship, becomes elastic the moment it becomes unstable.

Here’s the part that no one seems to be talking about:

By announcing tariffs against nearly every major trading partner simultaneously, the U.S. didn’t just strain relationships, it introduced dozens of potential partners to each other and gave them a shared reason to collaborate.

What might have been a series of isolated disputes has now become a catalyst for coalition-building. A fragmented global market is suddenly developing shared interests—not because they chose to, but because the U.S. forced them to consider alternatives.

Unlike with the U.S., many of these countries now have genuine consumer-level options. Canadian citizens only need to boycott goods from one country. For U.S. citizens to respond in kind, they’d have to boycott close to 90 countries. This increases risk for the U.S. through consumer behavioral asymmetry.

As a result, this isn’t just about economics anymore, it’s about credibility. When the U.S. is perceived as an erratic, extractive, and unpredictable trading partner, it ceases to be indispensable. It starts to become a risk factor.

Leadership, at the global level, isn’t about dominance, it’s about trustworthiness. When that breaks, even the strongest market position can become replaceable.

The lesson isn’t just economic; it’s behavioural. Trust, once lost, doesn’t simply revert; it reallocates.

My prediction: America will discover that it can’t set inelastic prices in an elastic market. The longer it continues to try, the more the world will learn how to live without it. As markets reel from the current correction, the U.S. may soon discover that the global demand curve has already moved—quietly, permanently, and off the chart.